Liubou Luniova: “A government afraid of freedom instinctively reaches for the baton”

This interview is part of the collection “Voice of the Freedom Generation”, a living testimony to the creative and civic presence of those who have not lost their voice even in exile.

Liubou Luniova. Gdansk, 2023. Photo: from personal archive

The collection tells the story of the laureates of the “Voice of the Freedom Generation” award, founded by the Belarusian PEN in partnership with the Human Rights Center “Viasna”, the Belarusian Association of Journalists, Press Club Belarus and Free Press for Eastern Europe endowment fund. The collection will be presented on November 15, 2025 at 5:00 PM during a discussion with the laureates of the “Voice of the Freedom Generation” award at the European Solidarity Center (Europejskie Centrum Solidarności, Gdańsk, pl. Solidarności 1).

There are miniskirts, Vladimir Vysotsky,[1] Bulat Okudzhava,[2] The Rolling Stones — and they lecture us about socialist competition

During our Soviet childhood and adolescence, everything was laid out for us: slogans and textbooks — one “correct truth.” But many have felt that there is something more. What was your experience?

I began reading at an early age, even before starting school, and quickly realized that accepting everything mindlessly was unwise, even harmful. You rush to music school with your violin, and everywhere you go, people tell you, “Let’s fulfil a five-year plan in three years!” Boring! Especially when, if not a Conan Doyle book, you at least have some science fiction at home. On Sundays, we children ran to the cinema for morning screenings. We either watched an idiotic film about a construction site or factory, or a cheerful documentary about the harvest or a party congress of some kind.

Meanwhile, it was the late 1960s. Stilettos, tape recorders, the twist, miniskirts, Vladimir Vysotsky, Bulat Okudzhava, the Rolling Stones, the Beatles… We had no interest in hearing about five-year plans! More so about socialist competition! No one could have inoculated us, still schoolchildren, against Soviet ideology better than the Soviet ideologists themselves. Maybe not all of us. But, as “Dear Leonid Brezhnev” used to say, my friends and I kept pace with the times.

Your school youth is not just about Minsk; it’s also Klichau with all its provincial charm. What did you notice about that part of the world?

I visited my grandparents every summer. It took almost the first quarter at school for my grazed elbows and knees to heal afterwards. There were so many different adventures. One day, we came across a place in the forest with an abundance of chanterelles. Suddenly, someone said, “Let’s get out of here quickly — this is a Jewish cemetery!” Why is everything overgrown with moss and shrubs? I was confused. At that time, nobody talked about the Holocaust. I started annoying my grandfather with questions. That’s how I learned that Klichau was a Jewish town before the war. Almost all of them were killed. The town was rebuilt and repopulated after the war.

A mark in memory. Could this be how another version of Belarusian history slowly unfolded?

Including through my family story. My grandfather was in charge of the school when he was reported to the NKVD. Allegedly, there was an icon on the wall of Darafei Soltan’s [the grandfather – trans. note] house. You can’t entrust children to a teacher like that! In fact, he was a staunch atheist. He once painted a portrait of my future grandmother and made a beautiful frame adorned with cornflowers and forget-me-nots. That artwork came back at him. To avoid being thrown in jail, he quickly enlisted in the army. Those in the military were not bothered. I thought about the informant, “What a scoundrel! He stayed with us, laughing, watching our young family with two little girls, and then acted so cruelly…”

And how did Grandpa’s military fate turn out?

The war started soon. He had experienced it all: his left hand’s fingers wouldn’t bend, and his arm was always bent at the elbow. He had orders and medals. After leaving the hospital, he found work at a military aircraft repair plant. However, he remained tight-lipped about the battles.

My grandmother willingly told me how her family survived the occupation in the forest. It had nothing to do with what was shown in the movies. The partisans who hadn’t managed to fall back behind the front lines were insiders. Yet, people still feared saboteurs coming from the mainland. They were stationed separately. Locals were mainly attacked because of sabotage. Those raids were horrible!

By the way, not all Germans were considered inhuman. One of them would bring food to the peasants when everyone got sick with typhus. He would often take my five-year-old mother in his arms and cry. He showed some pictures. He also had two daughters back at home. I wonder what became of him. Here’s my next mark: Not everyone is the same.

Additionally, there are significant differences between city and village life. Both adults and children are always busy with physical work.

It’s true: they kept noses to the grindstone. At the same time, though, they sang such beautiful songs when they gathered at the table! I wish I had recorded it. Those were long ballads. And no drinking.

Would you have been able to speak Belarusian if it weren’t for Klichau? It’s a myth that everyone in the eastern part of the country speaks exclusively “great and mighty Russian,” right?

No Russian was spoken there at that time. If you heard a child speak Russian, there was no doubt about it — a city kid came for the holidays.

What else do you remember?

I vividly remember the river and the footbridge that led to the village of Biorda. I would sit and admire the water lilies and watch the fish swim in the clear water.

The idyll came to an end with land reclamation. It was not an improvement, but rather the drainage of the earth. The forest springs were gone — and with them, the birch bark cups once waiting for a wanderer’s thirst. The Susha River, on whose shore the great-grandmother’s house stood, was gone. The Olsa River began to grow over with greenery because nitrates were scattered around and washed into the water. On top of that, people started collecting pearl mussels in sacks to decorate the foundations of shops and clubs. Some fool thought it was beautiful, but they were filtering the water. There were fewer spills each year, and the river became narrower, now just a trickle. Handmade decorations commissioned by the “Wise Party.” Another mark…

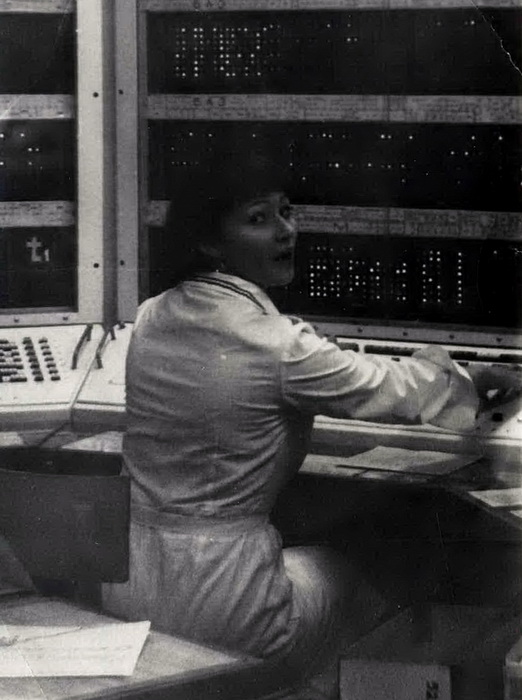

Liubou Luniova is an employee of the Institute of Mathematics of the Academy of Sciences. Photo: from personal archive

A normal person was framed as a criminal, while a criminal and a cynic were molded into saints

You worked at the Mathematics Institute of the Academy of Sciences and took an evening course in the History Department. Two completely different fields. Why such a wide range?

The era of computing machines had just begun. They were at the forefront of scientific progress. We had a BESM‑6 computer, the third one in the USSR after the machines in Novosibirsk and the Dubna monitoring system. It was just huge, occupying several large halls! The ground floor was entirely dedicated to a computing laboratory. Everything worked around the clock. I worked the night shift.

Nevertheless, history, especially that of the ancient world, made me way too excited. There was a lot of discussion among us back then about the “new chronology”[3] introduced by Fomenko and Postnikov. By the way, my friends who were pure mathematicians supported this theory. Goodness, we used to argue like crazy! What did the board look like in the differential equations laboratory? Graphs with straight lines, polylines, and formulas all over. If only the Phoenicians had known that their history was verified by mathematical modeling!

What was the primary outcome of education? Was it the capacity to question, to doubt, and to challenge established explanations? Have you ever felt that the profession itself presents a challenge, that it is bigger than just dates and surnames?

When my maternity leave ended, a laboratory assistant position became available in the Department of Southern and Western Slavs. I was going to work, pass my post-graduation entry exams, and begin writing my dissertation. I immediately became friends with Yury Drahun, Valiantsin Rabtsevich, and Henadz Dauhial at the faculty. They are such wonderful, interesting people, and I miss them so much. At that time, it was already clear that our views were diverging. For some, the environment was more important. They hurried to rewrite the history textbooks as Lukashenka ordered. Few people paid attention then. And this was not even a warning sign; it was a wake-up call.

Sooner or later, everyone encounters their first ban when the system orders, “This is not allowed!” What was your inner response? Did you accept or overcome it?

Isn’t participating in street protests a way of overcoming fear? When they were scaring people with snipers on the roofs, when you were going to a demonstration, and didn’t know how it would end. Everything happened for the first time. Even holding a Congress.[4] I remember Yury Zakharanka personally making sure that there were no “surprises” in the room.

Which example of family history influenced you more — staying silent or an open and honest, albeit risky, position?

I remember an episode, it’s worth writing a whole story about it. It was 1964. My mother was in the mine’s planning department office in Yenakiieve, with a portrait of Nikita Khrushchev hanging behind her. In the next office, someone was hammering something into the wall — and the frame fell. She picked it up by the loop, carried it into the corridor, and joked: “I’ll trade Khrushchev for two staplers.” As bad luck would have it, the head of the Party Committee was passing by. He had only four years of schooling and therefore hated technical engineering workers with higher education. So he took advantage of the moment: “On Friday, there will be a Party meeting — we’ll review your personal case. You can say goodbye to the Komsomol for sure, and I also hope you’ll be fired with cause.”

What a disaster!

On Thursday, with only one day left before the rigged trial, the colleagues suddenly approached her: “Lora, Lora! They said on the radio that Khrushchev was removed from office!” Mom was probably the happiest about the historical retirement.

I remember she was in her doctoral course, taking notes on Lenin’s works. Well, everyone had to do this, including me, but later. Dad asked why she didn’t want to join the Party. The reply was: “Go on, read what he’s written. Take this paragraph, for instance — do you get it? The leader of the world proletariat… It’s revolting, pure cannibalism!” I was dumbfounded. Vladimir Lenin was a saint to me. Since childhood, I had been surrounded by pamphlets and books about the heaven-dweller. However, when I began my own research of his writing, the situation became much clearer. That’s how it happened back then: a normal person was framed as a criminal, while a criminal and a cynic were molded into saints.

Liubou Luniova and future Nobel laureate Ales Bialiatski

Our protest allowed Ukrainians to avoid the war for a few more years

Belarus in the 1990s was a contradictory era: an explosion of opportunities, openness, and freedom on the one hand, and naivety, mistakes, and disappointments on the other. How does this time appear to you through the lens of a professional?

A window opened in it through which we could escape Russia. But you only understand this now, with all the events and time behind you. At the time, society was not ready. Ideology-poisoned Soviet minds blocked political will. How much did people know about the terrible role neighbors played in our fate? One thing was drilled into my consciousness: there is an older brother who is wiser, more beautiful, and stronger.

One day, I observed how the pupils of Suvorov Military College reacted to a film revealing new truths about the Tadeusz Kosciuszko uprising screened at the Writer’s House. They arrived noisy but left thoughtful. Well, at least they learned something. But how many people would see that tape? A couple of hundred or a thousand? They didn’t show it on TV. The truth was hard to come by.

If you were to write a true history of the last century, what would the main ruptures and fractures be? The most important events?

The countdown should start in 1914. We need material in school and student textbooks that addresses the enormous impact of the First World War on Belarus. In my opinion, the country suffered more than any other country. It was unable to recover before the next tragedy began.

Then came the period from 1945 to 1991, during which Russianization continued and Belarus became a testing ground for communism. The aftermath of the Chornobyl disaster also marked this period.

The third period spanned from 1991 to 2020. This marked the beginning of sovereignty, the collapse of independent politics, and the establishment of a puppet regime. It also led to the destruction of the country’s well-developed industry. Entire economic dependency on Russia. The demolition of democratic institutions, the lack of separation of powers, and corruption.

The fourth period begins in 2020 with the crackdown on civil society, repression, mass emigration, and the outbreak of Russia’s war against Ukraine. Belarus becomes a land under occupation.

Liubou Luniova. March 25, 2006. On Dzerzhinsky Avenue, when the authorities first used stun grenades against demonstrators. Photo: svaboda.org

Speaking of the 1990s and 2020 protests: are there similarities in the sentiments, slogans, and styles of solidarity exhibited during these two periods? Or, conversely, do they show that the country has entered a new stage?

The situation has obviously changed, as have the people. White ribbons were used at first, but they didn’t last very long. In an instant, national flags were seen everywhere. “Long live Belarus!” could be heard from every corner. In 2020, people were angry because of the pandemic and because they were treated like cattle. Not to mention the internet shutdown on election day.

They say there weren’t as many truly committed, idea-driven people at the marches as there used to be.

I disagree. Is a person who demands the right to choose instead of a piece of bread really not politically conscious? This is very much different from a demonstration by workers protesting tobacco shortages. The people longed for freedom and democracy — and in such an extraordinary way! The posters they created were remarkable, and the sense of solidarity was incredible.

After those events, we were taken aback when Ukrainians asked, “What’s wrong with your president?” They still don’t understand. Thanks to our protest, they were able to live without war for a few more years.

Modern-day repression is often compared to Stalin’s. Is it a fair statement? Does this actually provide genuine analytical insight into the situation, or is it instead a metaphor that emphasizes the magnitude of the cruelty?

The parallels appear valid, as the statistics of the victims will not differ significantly, even in percentage terms. Today, there are probably few families who haven’t been swept up in the crackdown. Someone was beaten or fired, someone was in detention, or paid a fine. Can life under constant surveillance be considered normal? Belarus is going through a terrible period. Even regime supporters are occasionally punished.

It seems to be the opposite, though. Their day has come.

I think it really hit everyone. After all, life should have been much better without the drastic change. A bunch of scoundrels is just a drop in the bucket.

What is immune to repression or propaganda?

The desire to be free.

Liubou Luniova. Photo: from personal archive

“Ms Luniova, some Christ guy was speaking, the ministry is losing it. What nonsense did he come up with this time?”

What does it cost to be one of the leading chroniclers of the protests? For years, you stood between the opposition and the regime, between the drive of the streets and the blows of the baton. What is it like to bear that — not as a symbol, but as a living person?

It’s interesting what you said about being a living person. There were moments when I genuinely just wanted to stay alive. In 2006, on Dzerzhinsky Avenue, they were shooting stun grenades and brutally beating people. I returned to the editorial office with blood on my beige suede boots. Not to mention 2020 — it’s hard to keep your composure when you watch people being beaten and dragged across the asphalt by their feet. Working on the radio exacerbates the situation because you need to stay close to the epicenter of events so listeners can feel the atmosphere and hear the injured’s screams and the anger of the security forces.

I’ve heard more than once that even the police treated Luniova with respect. How would you explain this phenomenon? Is it the result of your professional endurance, personal courage, or the ability to communicate with security forces as people and not enemies?

Yes, it was interesting to hear the comments from the seniors, majors, and colonels. Still, there was something unusual about their attitude toward me. High-ranking commanders were always present at opposition rallies, where they listened to speeches. And later, when there was no dispersal, they could come up and ask, “Ms Luniova, what was that report that got everyone so worked up? That guy, what’s his name… well, some Christ guy was speaking, the ministry is losing it. What nonsense did he come up with this time?” In a nutshell, I would tell them what Christos Purguridis, the PACE Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights, said about missing people in Belarus. We were both interested in the event because international observers had indeed put the Interior Ministry on its toes. I’m not sure why they spoke to me with such loyalty.

We actually lived in another country until 2020.I would reach out to various police authorities for comments. Once, the head of the criminal police department remembered that he had studied special classes at a Belarusian-language school and gave a comment “in the language” to Radio Liberty in Belarusian. This is unthinkable now.

What a story! Apparently, it’s not an isolated case.

One day, after another crackdown on the action on Kastrychnitskaya Square, the commander of the SWAT unit told me: “Do you have any protective equipment? You can get hit on the head.” “My weapon is a dictaphone, a pen, and a notebook,” I responded. The editorial office provided us with small dictaphones with large, heavy microphones. He picked up the device and tapped himself on the head. “Oh well, that’s a good weapon.”

Couldn’t we consider it a beautiful metaphor to say that, at times, Luniova’s mere presence was sufficient to deter the aggression of the security forces?

The nature of that moment is problematic for many to grasp, but years ago, the security forces still tried to maintain a respectable appearance. “We are law enforcement officers.” Yeah, right… But they were indeed ordered not to make brutal arrests in front of journalists for a certain period. I really noticed that. The closer we got, the more they controlled themselves.

We, the Belsat journalists, once went to a meeting with the company’s management in Vilnius. At the same time, many people went to a Siarhei Mikhalok concert. The border crossing was packed with buses. We’re late. My colleagues would insist, “Why don’t you go talk to them and ask them to make an exception for us?” But border guards aren’t police officers! They wear a different kind of uniform. Still, I pulled myself together and went for it — I said, “We’re not part of the dancing crowd like the others; we really need to hurry.” They looked at my journalist ID, saw my last name, and surprisingly let us through.

In short, various things have happened, and I can’t quite explain why. Among other things, it might have been because I was constantly reporting on acute events that everyone found interesting.

Isn’t there a subtle show of respect for women in dire situations, especially when it involves a prominent figure?

Hah! Sometimes, the situations were completely anecdotal. The Maskouski District Police Department employed a specific character. He started intimidating us in the hallway on the way to court. He swore and behaved aggressively. I reprimanded and asked him to lower his tone. He responded, “Don’t you dare to interfere!” “Is that how you talk to all women?” “Ms Luniova, you’re not a woman to me. You’re worse than Zianon Pazniak!”[5]

To him, Zianon was apparently the epitome of all the democrats’ worst qualities.

In this regard, I have a question: What is it like to work for many years in an environment dominated by men, such as in science, journalism, or human rights? Did you ever feel a double burden? When it comes to proving one’s competence, does a gender barrier make it a professional challenge that requires twice the effort?

This problem persists in certain contexts. The situation is gradually improving, though. As a rule, it was about money. The belief that men should be paid more is a banal manifestation of a patriarchal society. I would also like to mention the women’s marches and how the women broke through the lines of riot police. How they were beaten and dragged into police wagons, and how they bravely endured it all. That’s what complete gender equality looks like.

Liubou Luniova

It took me a long time to recover: I was defeated — but they had their lives taken away…

The feeling that you need to be right there, right now, next to that person — where does this professional instinct come from? Is it from the profession of a historian, who looks for signs in detail? Is it from the experience of a human rights defender, who always sees the person behind the fact? Or is it from personal intuition?

It seems to me that, as events develop, some details sometimes become noticeable on their own, and you just need to look closely at the stories. Everything is unfolding at the event site. I couldn’t have just worked from the office. I always needed to feel, smell, taste, and hear conversations, as they say. Many things are not included in the report; they remain behind the scenes. However, they are registered by your memory and gradually form a system of observation, sensation, and understanding. That’s how you start to see the pattern.

What is the purpose of journalism during protests? Is it merely the detached registration of facts, or is it also an attempt to make people feel like their voice has been heard and their dignity has been acknowledged?

A journalist should remain impartial. And it’s tough. This is especially true if everything is developing rapidly. To ensure clarity, it is essential to depict every element in great detail. During the 2020 protests, we had to consider our safety, which complicated matters.

I am grateful to those who recognized and appreciated your working conditions. One day, I was standing on a porch when a police officer started pointing his gun at me. The feeling of helplessness possessed me. Suddenly, the door opened, and a man pulled me inside. Then we heard the sound of a bullet striking the door. Later, I received a shell casing shaped like a bomb as a souvenir. This is the best recognition.

Not only do you save others, but others save you as well? Can you recall moments of a powerful emotional connection with the people you interviewed, whose stories you explored?

I had to deal with those who were sentenced to death.

In what way?

Their relatives and friends brought notes from them asking me to look into the case. Eight stories. I would go through every agency every time. I studied the case files and met with the lawyers. There were so many inconsistencies in six of their cases that even I, not being a lawyer, could see that the evidence was far from conclusive. It gave me energy — the desire to look for facts and arguments to help save those poor souls. And it was a big blow when they were still shot. Every one of them. Almost in one day. Despite the involvement of various international organizations, applications were submitted to the Supreme Court and the Prosecutor’s Office requesting additional proceedings and a stay of execution. But all in vain. It took me a long time to recover: I was defeated — but they had their lives taken away…

You began monitoring law enforcement agencies during the late Soviet era, when the police appeared more sluggish and timid than cruel. Do you remember when their actions transitioned from policing to open violence?

The brutal crackdown on the 1995 rally following the referendum immediately comes to mind. Students hung the flag of the BSSR on the toilet at the Yanka Kupala Theater. That was the beginning. At that moment, I was struck by how people in tracksuits could treat participants in a peaceful rally like that. After that episode, it followed a well-trodden path. Detentions, beatings of detainees, insults…

You spent three decades reporting on repressive mechanisms. How has it evolved from the Soviet script to authoritarian practice?

The practice of making arrests and bringing criminal cases against people protesting in the streets began to take shape in 1996, when the authorities decided to stop the protests by any means necessary. It should also be noted that these graffiti, pickets, demonstrations, rallies, and national flag hangings posed a threat to Russian expansion.

One example is the Freedom March in 1999. The government of the time deemed it impressive, and thus someone was to be held accountable. But that someone had to be depicted as a harmful troublemaker, one who misguided the public. Then, Aliaksandr Zimouski[6] announced on TV that it was a “herd of scumbags.” They also needed to demonstrate that the security forces were the ones who “suffered.” Cases were swiftly opened, and Valer Shchukin, along with Mikalai Statkevich,[7] were put on trial.

Everything has changed completely. Now, all there is is endless repression, and they don’t even try to create the appearance of legality. Police brutality turned into authorized lawlessness.

Liubou Luniova

Does the Belarusian legal system still operate under the same logic as before? Even if the forms have changed?

The former chairman of the court told me in the late ‘90s that he was summoned to the district executive committee and reprimanded for imprisoning a member of the Communist Party. And no one seemed to care that the offense did not allow for any alternative measure. In post-Soviet Belarus, Sovietism is still very much alive because they tried so hard to force our country into the stall, the USSR. The Supreme Court chairman ordered that sentences under criminal articles should not be overturned. You can write as many appeals as you want, but it won’t do any good. Cancellations are extremely rare. The rule of law is in a terrible state — and that’s why we have what we have now. The most important thing is the court’s chairman’s word and opinion. All administrative matters are decided on in advance in his office. But does it really matter who does it and where? It would be more honest if they just read out the list right away and immediately announced who gets how much time and under which articles…

Can human rights defenders really save evidence for the future in such conditions? Is there any hope that the documents gathered by the Viasna Human Rights Center will one day serve as evidence in a future trial of the regime, rather than merely ending up in the archives?

Absolutely. The media’s reporting and human rights activists’ monitoring are evidence of government crimes. Those responsible for gross violations of national legislation and international law must be tried.

Law enforcement officers are fired for being too soft, not too tough. So they break away. From the law and from the people

Over the past 30 years, numerous heads of law enforcement agencies in Minsk have changed, and each has set their own tone for their units’ work. Can we say that cruelty depends on personality? Or did the system grind down even those who initially remained “simple” people, even those in uniform with large stars?

A lot depends on the head of a particular department, including discipline, behavior, and treatment of protest participants. I observed that, with each new commander’s arrival, the situation with the riot police only got worse. After all, they have their own internal procedures. In our country, security forces are criticized for being either too lenient or not strict enough. The judge may be punished for a fair verdict, but not the other way around. So they break away. From the law, the legislation, and humanism. From the people.

Were there any instances in which police officers acted unexpectedly humanely? For example, they warned protesters instead of beating them, or simply turned away.

After being arrested and transferred to a different detention facility, I asked the guard to open the “feeder” because the cell was unbearably stuffy. He replied, “I can also open the window.” He entered the cell with a metal bayonet and let in some air. This generally violates the instructions. You cannot enter the cell, especially alone. We likely encountered a young soldier. Since he was so polite, I asked him to get my glasses out of my bag, which was among the confiscated items. I couldn’t read without them. He fetched me the glasses, too. And another one, when we were taken out for exercise in the courtyard, reacted to my words — “Ah! I need to put my hands behind my back. I just can’t get used to it…” — by saying, “What are you talking about? No need for that…” He stood out against the backdrop of omnipresent monsters.

The French Revolution is associated with the guillotine, the Russian Revolution with blood on the streets, and the 2020 Belarusian Revolution with torture in detention centers. Why do these cruel scenarios of human history repeat themselves during times of change? From the perspective of human nature, can we speak of a specifically Belarusian tradition of fear and war memory that transforms into political violence?

There’s no logical sequence to this. The French Revolution finally produced positive results: the monarchy ended, the Declaration of Human Rights was adopted, and class privileges were abolished. It demonstrated a new way of life to other countries.

So, did the 1905 bourgeois revolution in Russia have positive results?

Yes, the State Duma was established, political parties were legalized, and the people’s situation improved. We can even speak of the preconditions for the emergence of civil society.

For that matter, the 1917 Revolution ended the era of autocracy. Political prisoners were granted amnesty, the death penalty was abolished, and freedom of speech and assembly was declared. Solid advantages, right?

No, of course, the results were disastrous, but you must agree that there was an opportunity for this country to become humane finally. Then a gang of Bolsheviks seized power — almost without bloodshed by the way — and climbed to the top, drowning all the newly formed republics in tears. The exact number of people who were killed in labor camps and prisons is still unknown.

Liubou Luniova

What lessons can be drawn from 2020?

Even though it wasn’t a revolution, Belarusians felt themselves to be a nation — a force. They discovered their national dignity. We didn’t take to the streets to demand bread or land, but for freedom. And we wanted it so profoundly that no cruelty can crush that desire. It will come. Inevitably.

According to psychologists, every person has an aggressor and a defender inside them. What do you think prevails among Belarusian security officers, based on what you witnessed?

At the moment, security forces are recruiting the wrong people to serve in that capacity. They enlist to receive free apartments, higher salaries, and privileges. Who would want to serve in a hell like this if they grew up in a normal family, communicated with normal people, and saw what was happening?

When change comes, the state — and all of us — will face a significant problem: what to do with them? This job results in a mental disorder. Many of these young “baton carriers” will eventually get married and have children. I am confident that we will figure out the economy issued faster than such matters. There are thousands of them…

Compiling all of your reports into one volume would create a history book documenting state violence in Belarus. What should it be for future generations: a warning, a verdict, or a confession of that era?

I think there will be several substantial volumes. All of them illustrate what happens to a country when outsiders establish a dictatorship based on power and batons.

The project “Voice of the Freedom Generation” is co-financed by the Polish Cooperation for Development Program of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland. The publication reflects exclusively the author’s views and cannot be equated with the official position of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland.

[1] Vladimir Vysotsky was a Soviet singer-songwriter, poet, and actor who had an immense and enduring effect on Soviet culture. He became widely known for his unique singing style and for his lyrics, which featured social and political commentary in often-humorous street jargon.

[2] Bulat Okudzhava was a Soviet and Russian poet, writer, musician, novelist, and singer-songwriter of Georgian-Armenian ancestry. He was one of the founders of the Soviet genre called “author song”, or “guitar song”, and the author of about 200 songs, set to his own poetry.

[3] A pseudohistorical theory proposed by mathematician Anatoly Fomenko who argues that events of antiquity generally attributed to the ancient civilizations of Rome, Greece and Egypt, among others, actually occurred during the Middle Ages, more than a thousand years later.

[4] National Congress in Defense of the Constitution in 1996 (attended by 1,500 participants and 130 journalists from Belarus and abroad) adopted a resolution calling for Lukashenka’s removal from power.

[5] A Belarusian nationalist politician, archaeologist, and pro-democracy activist. He was a founding figure of the Belarusian Popular Front and served as the chairman of its parliamentary fraction in the Supreme Soviet of Belarus from 1990 to 1995.

[6] A Belarusian politician and former media executive and TV host, accused of being one of the key propagandists of the authoritarian regime of Aliaksandr Lukashenka.

[7] Two lifelong opposition members who started their political career in the early ‘90s.

@bajmedia

@bajmedia