Valer Karbalevich: “Our history is like a mirror; it reflects both defeat and chance”

This interview is part of the collection “Voice of the Freedom Generation”, a living testimony to the creative and civic presence of those who have not lost their voice even in exile.

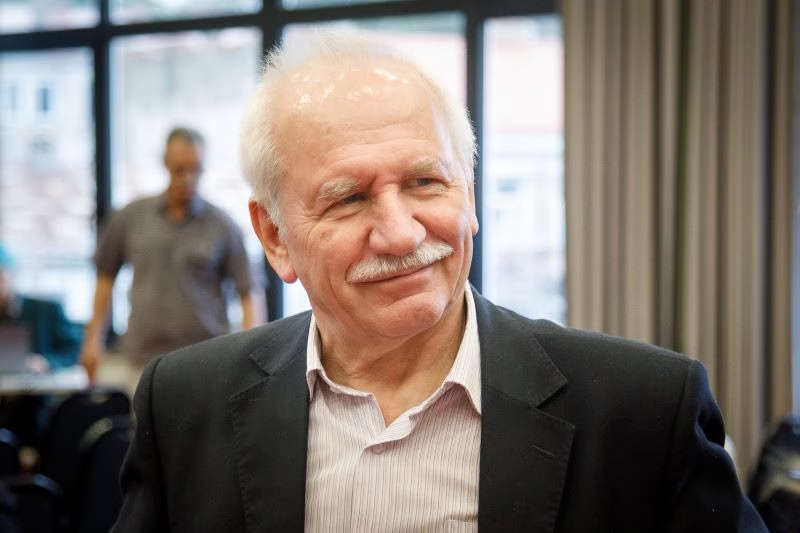

Valer Karbalevich at the conference “Belarusian Journalism: Where Tomorrow Begins”. Vilnius, September 16, 2025. Photo: BAJ

The collection tells the story of the laureates of the “Voice of the Freedom Generation” award, founded by the Belarusian PEN in partnership with the Human Rights Center “Viasna”, the Belarusian Association of Journalists, Press Club Belarus and Free Press for Eastern Europe endowment fund. The collection will be presented on November 15, 2025 at 5:00 PM during a discussion with the laureates of the “Voice of the Freedom Generation” award at the European Solidarity Center (Europejskie Centrum Solidarności, Gdańsk, pl. Solidarności 1).

Waiting for the gun carriage parade

In political science terms, every individual passes through a process of socialization. Can you recall the early influences (family, village community, education) that shaped your interest in political science?

My generation lived through very different eras: the deep Soviet Union and the late Brezhnev period, the time of so-called developed socialism and stagnation. Those were the circumstances under which I was socialized. Then it seemed like it would never end. When the General Secretary, who was supposedly programmed for immortality, finally died, we watched the solemn funeral broadcast and wondered what would happen next. Brezhnev was gone, but there were so many party clones who could take over and keep the system alive.

We still had to live long enough to see the gun carriage parade on Red Square.

Right. My life began back in 1955. It started in the Kostroma region of Russia.

The year was deeply symbolic. After Stalin’s death, Khrushchev steamrolled the party, and Malenkov lost control of the government when Bulganin pushed him aside. The monolith cracked again, and it already looked like an omen of future changes. But let’s get back to your roots: Are you Russian?

My Belarusian parents were drawn northward, seeking employment opportunities that promised higher salaries. My father was a chauffeur from the Starobin District (now Salihorsk), and my mother was a teacher from the neighboring city of Slutsk. They lived in the north for two years before returning to Belarus after I was born. So I spent my childhood and youth in the Slutsk District. I became interested in politics, so it was no coincidence that I enrolled in the History Department at Belarusian State University. However, the attempt was unsuccessful; I failed the competition. I spent a year working in construction and then tried to enroll again. I graduated from university with honors.

And despite this, you were assigned to work in the provincial Horki Agricultural Academy? Yes, five years in the eastern Mahilou region. Then, I pursued targeted postgraduate studies in the capital, followed by 10 years at the Belarusian Institute of Agricultural Mechanization — now the Belarusian State Agrarian Technical University.

Did you teach the history of the CPSU?

As was the joke at the time, the course’s name changed depending on the prevailing party line. During Perestroika, for example, it was first “Political History” and then “History of Belarus,” reflecting changes in political processes.

The Institute and the Academy trained personnel for rural communities and formed the future provincial intelligentsia. Were there people among them who thought outside the box or were capable of a different reasoning?

Do you mean civic political consciousness? The rural elite of that time were all part of and supportive of the system. Before the beginning of Gorbachev’s Perestroika, I did not notice any significant changes in their consciousness.

This is a paradox because the rural areas changed rapidly in the 1960s and 1970s.

I still remember the times when they harvested grain in collective farms with sickles. At the same time, I witnessed a rapid process of widespread mechanization. When I was in school, there was still no electricity in my village. I did my homework by the oil lamp. But in the blink of an eye, a technological leap occurred, and urbanization began. Schoolchildren saw a village full of people. Then, in the 1970s, young people started leaving, and the rural population began to age.

It’s worth supplementing the statement with some observations of the process…

Perhaps most importantly, as rural areas became depopulated, their vitality began to fade as well. Previously, there were amateur art activities, concerts, and competitions. The vast majority of it vanished as people started to depart. Meanwhile, it became clear that the collective farm concept was completely outdated, prompting people to migrate in search of a better life. Those who stayed typically didn’t have the resources to choose otherwise.

Was the mindset of village people different from that of city dwellers? How much? And in what way?

In my view, the difference in mentality between social groups at that time wasn’t particularly pronounced. I wouldn’t speak of any significant divide. Perhaps the agricultural sector was slightly more conservative. For example, during Perestroika, our institute was the most resistant to change. Both students and teachers. The rural intelligentsia did not concern itself with ideology. People solved personal problems and tried to improve their lives.

The broad politicization of Soviet society began only when Gorbachev declared that stagnation was not the norm but a disease — and that something needed to change, to be readjusted.

“Foam on the wave of Perestroika”

There were many temptations and red flags within the Soviet system for those who wanted to remain in the safe niche of teaching canonical history. What motivated you to challenge the existing equilibrium and step into the realm of public discussion about modernity? Was it a personal choice, or was it the energy of that era?

New historical processes are directly related to this, including the beginning of Perestroika and the advent of glasnost, among others. Like many others, I have evolved alongside society. There appeared a certain freedom — the opportunity to openly evaluate, analyze, and draw conclusions — which was very rewarding. You couldn’t afford that before.

Public organizations arose instantly and were then called “informal.” They were initiated from below, independently, and without the authorities’ permission, in contrast to the way things had been done until then. New media emerged, providing a platform for people to express their opinions.

So, the starting point of your “modern history” is not just your personal biography, but also a significant social shift?

Right, the totality — an avalanche of events. First of all, the rhythm and pulse of time could be felt in the Moscow press. The media sharply criticized the history of the Soviet system and the communist regime.

Can you think of any publication that caused the scientific community and you personally to change your minds?

For example, there is an article by Gavriil Popov[1] in the journal Nauka i Zhizn where he criticized the whole administrative system, not just Stalinism, for the first time in a Soviet periodical. Since the Twentieth Party Congress, the system has been considered good — it was Stalin who ruined everything. Then, suddenly, something completely different and deeper was voiced. Lenin also came under fire. In other words, the foundation of Soviet ideology — on which the entire communist system was built — was called into question. This marked the beginning of widespread criticism of the system as a whole.

The first independent informal circles in Minsk emerged at this time. Sovremennik grew from these circles. I became one of its founders. First, we met in apartments, but soon we began holding public discussions.

It was an attempt to break free from the Soviet sphere of influence and establish an independent intellectual space. Was this the first school of freedom, or merely an illusion of an alternative?

We were a group of intellectuals with a penchant for dissent. My good friends and fellow students, Viktar Charnou, Mikhail Plisko, and Raman Yakauleuski, were among us. During our meetings, we seriously discussed our experiences and challenges. As new people gradually joined the discussions, they began looking for a convenient space. Ultimately, Leu Kryvitski unexpectedly secured a room in the House of Political Education. People were drawn there like a magnet.

For how long did the unrestrained period persist?

The debates were so impactful that the authorities quickly mobilized teachers from the Higher Party School to shut them down. The ideological counterattack failed, and then the infamous article “Foam on the wave of Perestroika” was published.

They started to investigate: who had initiated this process? It turned out to be an associate professor from the Department of CPSU History! A massive scandal broke out, and they dissected us at a party meeting. The party secretary called Charnou and me in and summed it up: “You are smart guys, but you’ve just ruined your careers for life.”

Much later, I came across a special resolution from the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Belarus that mentioned my last name. Then, a personal data sheet containing my biography and a summary was sent to the party organizations. The conclusion read, “This is one of those who destroy the Communist Party.”

However, it didn’t take long for the system to collapse.

So, can you call yourself a first-wave democrat?

I would frame it differently. Even under the communist regime, our Sovremennik club became one of the first forms of civil society.

Let’s recall a few more notable groups from that period. From a different sphere, perhaps, but still well known — Talaka, Tuteishyja…

They were primarily guided by the national idea, which led to the establishment of Belarusian nationalism. Soon after, the Belarusian Popular Front and several social democratic organizations were born from it. This process was unfolding from multiple perspectives.

Valer Karbalevich at the conference “Belarusian Journalism: Where Tomorrow Begins”. Vilnius, September 16, 2025. Photo: BAJ

The liberal trend was founded on civil and political freedoms. The national idea didn’t inspire us much back then.

The Democratic Platform is something worth mentioning when it comes to your wing.

Right, to a large extent, the United Democratic Party of Belarus originated from that group. I helped create it in 1990, before the collapse of the Soviet Union. However, when it became clear that this force was bringing about the destruction of the Red Empire, many people, including leaders, stepped aside. Some people were unhappy with the shift toward a European path, toward the West. In today’s terms, the political supporters of the “Russian world” had already begun to emerge back then.

And what happened in the realm of official ideology?

When real political competition emerged, the old, familiar structures revealed their inability to compete and began to crumble. After all, they were not prepared for a political struggle, nor for the fight for their ideas. The Communist Party, the Komsomol, and the trade unions all surrendered without much resistance. The situation is almost identical to what happened in 2020. In times of acute political crisis, organizations created by the authorities simply disappear from the arena. They were made for a different purpose.

To be the façade?

To exert control over the most critical areas of public life. However, controlling is not fighting.

From experts to “extremist centers”

There were also transformations in the democratic field: something changed quickly, and something new appeared immediately. In 1993, Anatol Maisenia — a journalist and one of the first Belarusian political scientists — created the East-West National Center for Strategic Initiatives and invited you to join. Was that moment a turning point in your career, or an entryway into a completely new field where the first guiding principles of civil society were being formed?

That was a new reality. Maisenia noticed my activity on independent media, where I commented on political processes and events, and he offered a collaboration. The Center developed and grew rapidly. We held many vital conferences that became significant events in social and political life. This included the participation of Stanislau Shushkevich, the head of the Supreme Council; deputy prime ministers; the Minister of Foreign Affairs; generals from the Ministry of Defense; scientists; and Western politicians. The Center has had a significant impact on the country’s socio-political processes through its research.

It reached the point of absurdity: precisely this effectiveness irritated some of our opponents within the opposition’s own camp. The East-West was supposedly pro-government if the officials approached us willingly. “Look, they’ve already implemented a few ideas. They’re lobbyists for the bureaucracy and Kebich’s[2] apparatus. Tally-ho!”

Efficiency always causes jealousy. But what was the honest criticism behind the façade?

Our colleagues overlooked the moment. They did not understand that the new era brought new players to the information field whose role was to provide expertise. It was an unexpected phenomenon. People without significant levers, but with extensive knowledge and unconventional perspectives, became influential. It started in Moscow, where experts in economics, politics, and social work have become trendsetters in various vital areas with the help of the media.

In addition to Popov, other famous figures of the era include economists Abel Aganbegyan, Leonid Abalkin, and Stanislav Shatalin.

The early 1990s, when independent Belarus emerged and the Soviet Union collapsed, coincided with a trend we started. Scientific expertise has become an essential factor in shaping social and political processes and public consciousness. Back then, newspapers and magazines had huge circulations. People read a lot, watched, and listened to live broadcasts of essential discussions for days on end.

But today, that institution has fallen below ground level. What caused its downfall? Was it exclusively the state’s malicious intent?

The latter had a significant influence on the process. However, I would also like to point out that the development of communication technologies has led to “expert” assessments coming from almost anyone with a camera or microphone and a computer. Profanity and populism were abundant. The demand for quick and simple answers has destroyed the depth of analytics and, in a sense, the concept of expertise itself.

However, the authorities “appreciated” its weighty voice.

Analytical centers, an influential part of the opposition, were targeted by Lukashenka as soon as he became president. A criminal case was opened against us after 1996. We had to shut down and establish a new brand: the Strategy Analytical Center.

At that moment, doing politics had already transcended the legal realm. In a country where the government was openly breaking the rules, was it possible to stay out of politics?

At one of the meetings, the “young” president announced that the opposition receives money from abroad through three centers: the Soros Foundation, the Grushevoy Chornobyl Relief Foundation, and us. This coincided with the death of Anatol Maisenia. It was the beginning of an era of total “crackdowns.”

What was its first turning point?

Of course, the 1996 referendum. It completely transformed the constitutional architecture, making the state super-presidential. The “plebiscite” took place in an absolutely illegal manner. Constitutional law experts called it a coup d’état, marking the beginning of Aliaksandr Lukashenka’s classic authoritarianism.

What tools were employed to reinforce the new political order? Despite the change of historical scenery, what has remained constant in this process for years?

Repression. The systematic destruction of all institutions capable of creating alternatives. This includes think tanks, independent media, and NGOs. They did not disappear completely. Instead, they were driven into reservations and lost their influence over political decisions. This is an example of authoritarianism at its finest. Today, in 2020, we are already facing totalitarianism.

Valer Karbalevich at a meeting with Mikhail Gorbachev at the Minsk IBB Center

1994 election: Industrial echo or rural conservatism?

It is often said that the first phase of his rule was quite liberal for many because of the social contract: the government provides stability and minimal welfare in exchange for society’s silence. Was this a fancy scheme or political science fiction?

Deception is inherent in the concept of a “social contract.” It’s more of an abstract political science construction than a reality. It’s a disguise — a way to cover up what’s really happening. As a result, Lukashenka relied on more than just repression; he also counted on the social model of life he had created.

At one point, the “chief designer” began claiming that it was a role model, not just a local phenomenon. This was said to have become an alternative to the post-communist transformation.

In fact, its essence lies in exchanging cheap Russian gas and oil for “kisses.” For “integration kisses,” Belarus received a share of Russia’s fossil fuel revenue. This resulted in relative economic growth. However, the effects were felt throughout the entire post-Soviet region, not just in Belarus and Russia. Lukashenka capitalized on this trend and reaped certain dividends: people were willing to tolerate authoritarian methods because life “had improved slightly.”

In models like this, the first person always became the central figure. The well-known phrase “I am the state” is very suitable in the case of Belarus.

Many forms of personalism have existed and will continue to exist. The outcome depends greatly on the individual. In any personalist regime — and there have been many around the world, with more still to come — much depends on the figure at the top. Lukashenka indeed exerts significant influence over political processes. Take 2020, for example. Under the pressure of the post-election protests, I think many dictators would have resigned. The Belarusian one picked up a machine gun and a bulletproof vest, saying he would defend his power to the end.

You wrote a book about him and created one of the most accurate portraits of Lukashenka. Which style, psychological, and management model features were evident as early as 1994? What did analysts, the media, and voters overlook?

He successfully capitalized on the widespread disappointment with the reforms. Most of the population viewed the complex process as ugly, chaotic, and even anarchic. Lukashenka, the former director of the Haradzets State Farm made a firm promise: “I’ll straighten things out and get back what you lost.” To many, the still-living Soviet sentiment seemed a saving grace.

What about the new civil movements and political intellectuals? Did you just observe the rising influence of a populist politician from the sidelines? Why didn’t you manage to convey your ideas? Was there really a gap between the elite and the electorate?

Lukashenka gauged public sentiment and won the only democratic presidential election in Belarus. Admittedly, he relied on popular support in his fight against the opposition and other institutions, such as the Supreme Council and the Constitutional Court.

My question is about something else: Why didn’t the intellectuals — the democrats — manage to reach the people?

Because the people resisted the changes that we, Lukashenka’s opponents, supported, it’s no coincidence that Ales Adamovich[3] referred to Belarus as the “anti-Perestroika Vendée.”

But why did this happen?

The period from 1950 to 1970, known as the industrial revolution, was indeed a time of significant social development for Belarus. The republic was far ahead of other regions of the Soviet Union and many other countries around the world. Millions of Belarusians moved from the countryside to the cities. They settled into comfortable apartments by the standards of the time. Their quality of life improved significantly. This is a powerful argument. This transformation took place over the span of one or two generations. People who stood in line at the ballot boxes in 1994 witnessed it.

When Gorbachev announced that there had been a period of stagnation before him and that the state was in poor condition, Belarusians did not understand him. After all, they remembered the time under Piotr Masherau[4] as the best time of their lives. That is why they did not support the calls for reforms. Lukashenka tapped into this sentiment by offering to restore the “lost gold” of the Soviet era — an attractive promise for the electorate.

Traditionally, this situation is interpreted differently: it is said that the 1994 vote reflects Belarusian rural conservatism. You are focusing on the inertia of the previous socioeconomic breakthrough. Did the unheard-of, large-scale industrialization of the BSSR have an impact?

That’s right. Stalin’s industrialization was violent and instead led to a deterioration in living conditions. In contrast, post-war industrialization in Belarus raised living standards. Besides, our region did not experience the same level of corruption as other regions of the USSR. Moreover, we had a charismatic leader, Masherau. Changes for the better were also associated with him.

Therefore, the Belarusian Popular Front did not receive the same level of support as it did in the Baltic States and Ukraine. All these factors combined strongly influenced the formation of the national idea. For example, the BPF was not as popular as the Popular Fronts in other regions of the Soviet Union, such as the Baltic States and Ukraine.

The conservative nature of Belarusian society influenced the outcome of the 1994 election and the country’s subsequent development.

Civil society: From desert lands to exile

When the first NGOs, foundations, independent editorial offices, and political parties began to emerge in Belarus, did people feel that these were more than just local projects — that they could lay the groundwork for a new country?

The potential was obvious. As old structures disintegrated, the socio-political landscape became barren. Given this context, it was essential to devise a new one.

A civil society is an essential element of a democratic country. In our situation, however, there was simply no room for maneuver. After all, the democratic process in Belarus was very brief and quickly collapsed. Consequently, the expansion of this niche was significantly constrained. For instance, it was linked to backing from foreign funds rather than domestic financial institutions.

After so many years without genuine elections, under intense pressure and dependent on grants for survival, could this be seen as a gradual depletion of civil society? In such difficult conditions, did civil society still have some kind of strategy — or should we rather speak of a merely reactive existence?

Unfortunately, the latter is true. Each structure was focused on its own survival and limited goals. There was no overarching strategy like “We will build a democratic Belarus through civil society.” Some people wanted to do this, but generally, everyone was doing their own thing. In an authoritarian system, it could not be otherwise. Such a system blocks and slows down the development of civil society.

The former totalitarian structures in Belarus have not yet fully collapsed. The powers and roles of deputy heads of ideology departments have increased dramatically within enterprises. Labor collectives are now both business entities and political units.

Can we say that during the brief democratic period, the civil sector evolved into an alternative to Soviet political institutions — a “parallel Belarus”?

In a way, yes. Over time, the Communist Party and the Komsomol were pushed aside, but there was no privatization. The public sector remained dominant. The economic system survived, which greatly limited the development of new civil institutions.

Now, let’s move from the past to the present. What about civil society in exile? Is it capable of shaping the country’s future?

The extraterritorial Belarus — a civil society in exile — has already become a tangible reality. It has been created and is operating. But we face serious problems.

The issue of influence on domestic political life is paramount. On the one hand, the Internet era has made emigration much stronger and broader than it was in Soviet times. Nevertheless, real scenarios of change will unfold in Belarus. No one can predict the outcome. External geopolitical factors play a significant role. They complicate both forecasts and current activities.

Valer Karbalevich at the conference “Belarusian Journalism: Where Tomorrow Begins”. Vilnius, September 16, 2025. Photo: BAJ

2020: Who/what was hit by the perfect storm

What happened to us in 2020? The government and civil society overlooked the civil explosion, which begs the question: where did it come from? What was the reason for this?

I can brag a little here. Parliamentary elections were held in 2019. Then, during the roundtable discussions, I said that, for the first time during Lukashenka’s rule, the number of his opponents had surpassed that of his supporters. Everyone criticized me at once, asking, “Where did you dream this up?” I answered honestly: “I don’t know where or how it will manifest, but the landscape of electoral sympathies has shifted.”

And it exploded just a year later. Then there was what is called a perfect storm: several important factors coincided at once.

The authorities’ reaction to the pandemic was unprofessional and dramatic. A genuine alternative emerged during the election — first Valer Tsapkala,[5] then Viktar Babaryka.[6] As a result, people with vastly different political ideologies and views found common ground in one sentiment: anyone but him!

So, has the classic Belarusian conservatism failed after all?

It was something else — specifically, the social processes that shaped the middle class. This group wanted to influence politics genuinely, and society sought to become a political actor rather than a mere object. We have evolved to the point where we demanded the right to choose, not just the right to vote in fake elections.

And what role did civil society play? Though ostensibly unnoticed, it was, in fact, like a “mole of history,” preparing the ground.

Yes, civil society has done a lot. Of all its institutions, however, I would single out the independent media. They played a crucial role in this critical situation. The authorities overlooked the advent of the internet, which eliminated the traditional monopoly on information. Non-governmental websites, forums, and platforms have taken over the unregulated digital space. They began to dictate the public agenda. In one way or another, a large part of the population used services offered by the Tut.by media outlet and by other editors and bloggers. The power vertical simply did not understand the changing situation. They underestimated the importance and potential of new media. In particular, since Lukashenka himself doesn’t live in the online world and doesn’t use a computer, he failed to grasp the political impact of modern communication technologies.

As for civil society as a whole, its greatness emerged in the events of 2020. The sheer number of neighborhood, residential, and professional chats is impressive, as is the phenomenal role of Telegram channels.

Hundred-thousand, two-hundred-thousand, even half-million-strong demonstrations could not fail to impress. But wasn’t it, above all, a moral community — united against evil, yet without clearly defined political goals?

In that highly politicized atmosphere, every issue took on a political dimension, the rigged election, the exclusion of Siarhei Tsikhanouski,[7] Tsapkala, and Babaryka from the race, the beatings of civilians, and many other factors — all of it culminated in a political protest. Everything was transforming in the process and becoming part of politics.

Let’s dwell on the trigger figures — Babaryka and Tsapkala. Is applauding them still an old Belarusian dream of having a “strong economic leader” at the head of the country?

That’s right, this attitude is deeply embedded in the national consciousness. The head is expected to be an executive with economic experience. These people supposedly understand others’ needs better and can fulfill their promises more quickly.

The example of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya negates this theory!

It’s a whole other story. After Lukashenka cracked down on all his real rivals, people were so angry that they voted for her, a woman with no political or economic experience. The vote was not a show of support for Tsikhanouskaya; it was a protest against Lukashenka.

Or, to put it another way: this was how people defended their right to dignity and their right to make their own choices. We are human beings, not cattle. We’re fed up — we want to live differently!

Yeah, one could reason in this way. Moreover, Tsikhanouskaya declared, “I’m not here to lead the country — I just want to ensure free elections are held.”

However, politics is not taken seriously in Belarus at all. A party leader feels like a joke. However, the head of a bank or a high-tech park is seen as an honest businessperson. This is because we lacked experience with real democratic elections.

Isn’t this reminiscent of Belarus’s success when its economy was growing and business executives were seen as heroes?

Absolutely. The public sector still accounts for nearly half of the entire economy. Therefore, the head of state is seen primarily as an administrator. That’s why Lukashenka continues to visit state-owned farms and factories, publicly lecturing local officials. This is all part of his political theater and his attempt to appeal to the electorate.

The epilogue

Following the convention of the genre, let’s revisit our starting point. You have been a university teacher for many years. Let’s imagine a situation: another lecture on the most recent period of our existence, given to tomorrow’s historians and political scientists. What would you tell them in conclusion? What maxim would you leave them with? What would you advise them to pay attention to — how to act, how to live, and how to assess what’s happening?

Dear colleagues, Belarusian statehood is still very young — only 35 years old. Neither the ideological, political, nor economic models have fully taken shape yet; they are all still being formed. That’s why the human factor plays a much greater role here than in countries with stable systems. We have the power to influence the processes taking place in Belarus today much more strongly. So I urge you: join in boldly, take part, make an impact, and seek out your own — our Belarusian — way!

The project “Voice of the Freedom Generation” is co-financed by the Polish Cooperation for Development Program of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland. The publication reflects exclusively the author’s views and cannot be equated with the official position of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland.

[1] A Russian politician and economist. He served as the mayor of Moscow from 1991 until he resigned in 1992.

[2] Viachaslau Kebich was a Belarusian politician and the first Prime Minister of Belarus from 1991 to 1994.

[3] A Soviet Belarusian writer, screenwriter, literary critic and democratic activist.

[4] A Soviet partisan, statesman, and one of the leaders of the Belarusian resistance during World War II who governed the Belarussian Soviet Socialist Republic as First Secretary of the Communist Party of Belarus from 1965 until his death in 1980.

[5] Belarusian politician and entrepreneur; former diplomat, ambassador to the U.S. and Mexico, and founder of the Belarus High Technologies Park. A key figure in Lukashenka’s 1994 campaign, he later became one of his main opponents, barred from the 2020 presidential race and sentenced in absentia to 17 years in prison in 2023.

[6] Belarusian banker, philanthropist, and opposition politician. Seen as the leading challenger to Lukashenka in the 2020 presidential election, he was arrested in June 2020 on politically motivated financial charges and later sentenced to 14 years in prison.

[7] Belarusian YouTuber and opposition activist known for his criticism of Lukashenka’s regime. He was arrested in 2020 shortly after announcing his presidential bid, with his wife Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya running in his place. After five years in solitary confinement, he was released on June 21, 2025, following a visit to Belarus by U.S. representative Keith Kellogg.

@bajmedia

@bajmedia