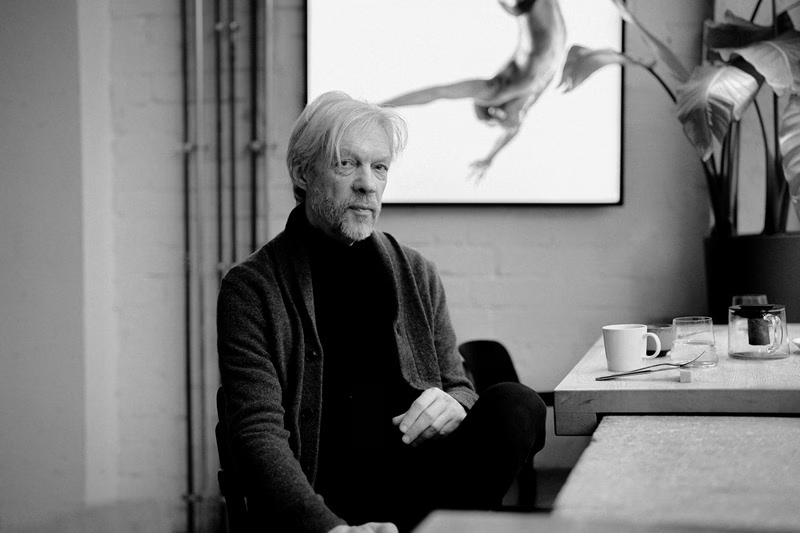

Maksim Zhbankou: Life, just life — traumatically beautiful

This interview is part of the collection “Voice of the Freedom Generation”, a living testimony to the creative and civic presence of those who have not lost their voice even in exile.

Maksim Zhbankou. Photo: from the Facebook

The collection tells the story of the laureates of the “Voice of the Freedom Generation” award, founded by the Belarusian PEN in partnership with the Human Rights Center “Viasna”, the Belarusian Association of Journalists, Press Club Belarus and Free Press for Eastern Europe endowment fund. The collection will be presented on November 15, 2025 at 5:00 PM during a discussion with the laureates of the “Voice of the Freedom Generation” award at the European Solidarity Center (Europejskie Centrum Solidarności, Gdańsk, pl. Solidarności 1).

Belarus in the 1990s: From the Soviet wreckage fair to the aesthetic revolution

When we look back at the 1990s in Belarus, we are tempted to view this period as either a genuine national renaissance or a chaotic fairground on the ruins of an empire, where underground postmodernism and Facebook folklore have become the defining symbols of the era. But what were the ‘90s to you?

It was more a personal transformation than a global turning point. Everything that happened to the country affected me personally. I was born in 1958, which makes me part of the late Soviet generation. We were prepared for the Empire’s collapse. We had witnessed its decline and experienced life under a totalitarian regime, stripping us of all freedoms, where culture was the only refuge. Western rock ‘n’ roll, club cinema, samizdat, and translated literature all contributed to shaping an identity. It was my own dissident project, and I did everything alone, outside headline communities.

However, alternative music, intellectual circles and street demonstrations were already a thing in Belarus at that time. What was your perception of them?

I saw people marching under white, red and white flags. I scrutinised the menacing armoured vehicles at the intersections. To me, however, it looked more like a performance than a personal struggle. I lived in autonomous dissidence, guided by intuition and emotion. It was only through my friendly relations with the Belarusian-speaking intellectual community that I started to feel like, “Hey, this is about you too!”

Who did you find particularly important in that community?

Valiantsin Akudovich, Ihar Babkou and Ales Antsipenka, of course, as well as colleagues from Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and the independent press. One day, I unexpectedly realised that all my best friends were Belarusian-speaking. All of them were obsessed with the idea of a new national design. I was primarily attracted to it as an art project and an aesthetic revolution. Narodny Albom (People’s Album), which I first heard back then, captivated me with its beautiful sincerity and touching aesthetic, rather than its sound quality.

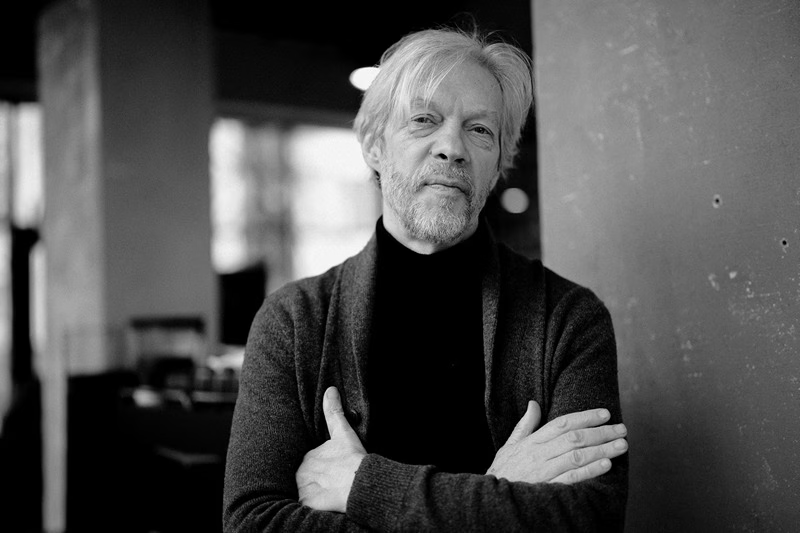

Maksim Zhbankou. Photo: from the Facebook

So it was aesthetics rather than politics or philosophy that defined your Belarusian identity?

Absolutely. I did not become involved because of Abdziralovich’s[1] ideas or political slogans. For me, all of this was revealed through artistic harmony, personal contacts and a particular way of thinking. In the absence of both official freedom and a robust state ideology, a unique zone of openness emerged — a realm of liberty, distinct and unparalleled. And so began my personal Belarusisation.

New sky: Above flags, across the soul’s horizon

To understand your personal transformation, let’s take a brief look at what you were doing before the nineties.

I was an ordinary Soviet philosophy teacher. I graduated from the Philosophy Department at Belarusian State University and went on to complete a postgraduate degree and defend my thesis. The university functioned as a factory churning out ideologically driven programmers and as a training ground for bureaucratic thinking. However, I opted for a different popular choice at the time: I delved into the methodology of scientific knowledge. My research focused on the early modern period, specifically the transformation of mass consciousness during the 16th and 17th centuries. It was my inner reserve, a space for autonomous thinking where I didn’t have to refer to some Party Congress on every occasion.

So, you were essentially living within the Soviet system but seeking ways to exercise subversive autonomy?

Exactly. When I got introduced to the Belarusian intellectual community in the 1990s through my work at the Soros Foundation and the Belarusian Collegium,[2] as well as through Radio Liberty, my personal dissidence was reflected in their models of autonomous existence. It was indeed a minority and niche culture. But it seemed incredibly beautiful and attractive. Despite not speaking perfect Belarusian, I felt like I belonged there. I was an insider. After all, a new sky suddenly opened up, not through the colours of national flags, but through a different dimension of existential independence.

You mentioned the philosophy department as a breeding ground for ideological cadres. Have you ever encountered any of these “real ideologues” yourself? Those who shaped the rules of the game and controlled student life?

My mother worked at the Institute of Philosophy; she knew them. I only witnessed what happened in our faculty. And we knew for sure: there was always someone from the secret services nearby. He could be an assistant dean — supposedly just a sexton — but everyone knew that this man was keeping a close eye on us.

We had international students in our philosophy department: Cubans, Poles, and East Germans. Back in the early eighties, when the Solidarity movement was in full swing in Poland, a small group of students got together and wrote an appeal to the dean’s office, collected some signatures, and asked for a few changes to how studies were organised. But the letter was viewed as ideological subversion. The immediate response was, “This is Polish interference, foreign manipulation, work of enemy agents!” They’ve begun a real hunt for the people who initiated this. Some were expelled from university, one was urgently drafted into the army. He later tried to resume studies, but this was refused. The guy committed suicide. He jumped from the sixth floor of the main university building. Directly onto Lenin Square.

Maksim Zhbankou. Photo: from the Facebook

What was stifling the lively atmosphere among the students, which should have been brimming with life?

It was the steady presence of something dark, hostile, and dangerous — the pressure of the official lifestyle and the constant need to demonstrate loyalty.

In the new intellectual environment I encountered after leaving BSU in 1994, there was no such hostility or distrust. The people who gathered were, of course, very different from one another. There were adventurers, talkers, thinkers, swindlers, wise men and crooks, all with their own ambitions and prejudices. But it seemed to be a normal, lively community. In contrast to the general decline in official circles and the hopelessness of being held hostage by a defunct empire, the Belarusian community was a real haven: cosy and comfortable. Although I realised it couldn’t significantly alter the bigger picture, for me it marked a personal step forward, opening up an entirely new dimension of movement and growth.

Collegium: A factory of new meanings

However, there were individuals within your circle who were actively engaged in practical opposition activities. Antsipenka, for example, who worked with you at the Soros Foundation. Or Aliaksandr Susha, who supported the Narodny Albom project, among others. Have you discussed these connections and felt their impact?

Susha is connected not only to Narodny Albom but also to Sviaty Vechar (Holy Evening) and Ya Naradziusia Tut (I Was Born Here). Everything here mattered, but politics remained uninteresting to me. I couldn’t see myself fitting in. So I began exploring unusual states of consciousness. My politics was an electronic music craze.

The Belarusian Collegium is a unique phenomenon in our history. What was its role? Can it really be considered apolitical?

It emerged following the dissolution of the Soros Foundation. The community surrounding Antsipenka, Akudovich and Babkou came together in a new format. The Collegium’s mission was no longer to resist politics openly — that was impossible. The aim was to create new mechanisms of consciousness. This educational project produced new meanings, terms and intellectual concepts. In fact, the small organisation operated as a national academy, as each program track had a significant cultural tradition and strong alliances.

Can this be considered as a form of the “invention of Belarusianness”?

Absolutely. The death of the Communist ideology left a total void. We stepped into this void, creating Belarusian thought and philosophy anew. We have demonstrated that critical and exciting thinking is possible in Belarusian. You can translate French postmodernists, and their works will not lose any meaning in the process — quite the contrary, they will acquire new ones. It was a place where everything — from music to philosophy — was being created anew. The lack of a central focus made the process explosive: the rock music, the magazine Frahmenty, the Collegium, the film screenings and the publishing projects all worked in parallel and in different dimensions. The post-Soviet nation’s matrix of meanings was emerging.

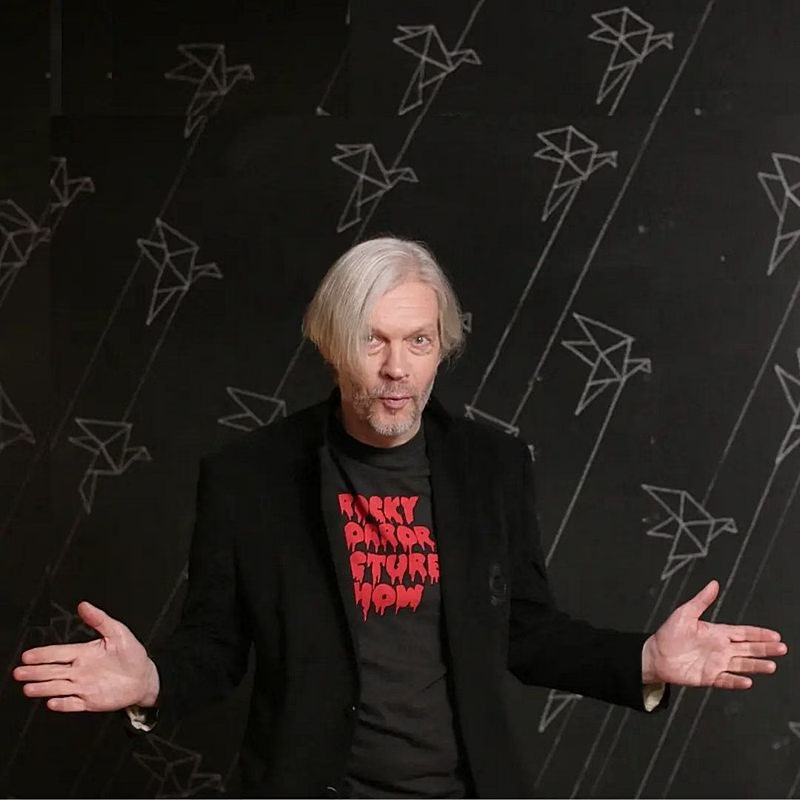

Maksim Zhbankou. Photo: Artem Lobach

To give us a sense of the scale, would you share some numbers? How many people attended the Collegium’s lectures and debates? Which graduates went on to become well-known figures?

It’s easier to name those who didn’t pass through us. For instance, almost everyone involved in the modern school of Western literature translation in Belarus comes from Andrei Khadanovich’s seminar at the Collegium. And this is just one example.

Amazing! Could you name a few more names to give us an idea of the scale?

The Collegium was designed to be a living community—an entwinement of individuals. Akudovich worked in the fields of literature and philosophy, while Antsipenka and I developed the media program track. Khadanovich, meanwhile, organised the translation workshop. Around each person, a distinct circle of like-minded people would form. Everyone brought their own models and visions. And out of this intertwining of individuals, a new intellectual reality emerged — a new cultural situation.

Groovy Belarusianness and new territories

You argue that the Collegium did more than just provide knowledge; it actually conveyed a fundamentally different attitude towards national culture. What was this attitude?

Our role was to broadcast a non-academic, non-Soviet and non-communist approach to national thought, tradition and culture. It was the birthplace of a new country and culture. That energy was infectious: we were inspiring young people to embrace groovy Belarusian culture. In fact, they joined in themselves. People entered the community and quickly started writing their own texts and working on projects.

Can you name the people who began their journey in this environment?

Sure. The late Aliaksei Strelnikau, an exceptional theatre critic; Pavel Sviardlou, head of Euroradio; and Siarhei Budkin, head of the Belarusian Council for Culture, all studied with me at the Faculty of Journalism. These are just a few of the notable figures. Some others joined as auditing students. These were small groups of around twenty people. But they were the best and most engaged — those who needed more than what public education could offer. We have put forward alternative models of existence, analytical approaches and creative viewpoints. They went beyond the Collegium, but it was with us that they got their first impulse.

Did you work openly, or did you keep to the shadows?

It was safer to stay inconspicuous. The authorities might have seen everything we did as dangerous. Back when I was working at the Soros Foundation, I was well aware that our communications were being monitored. You’re on the phone, and just two seconds later, a sharp clicking noise comes through. The connection is interrupted and then restored. One day, a colleague reached the breaking point and shouted into the phone: “Comrade Major, let me finish!” It was an obvious fact of life that everyone understood: you were being watched and could be crushed. That’s why we adopted a guerrilla approach. That’s what saved us. Such small philosophical communities were beyond the government’s reach. There was a chance, and we took it.

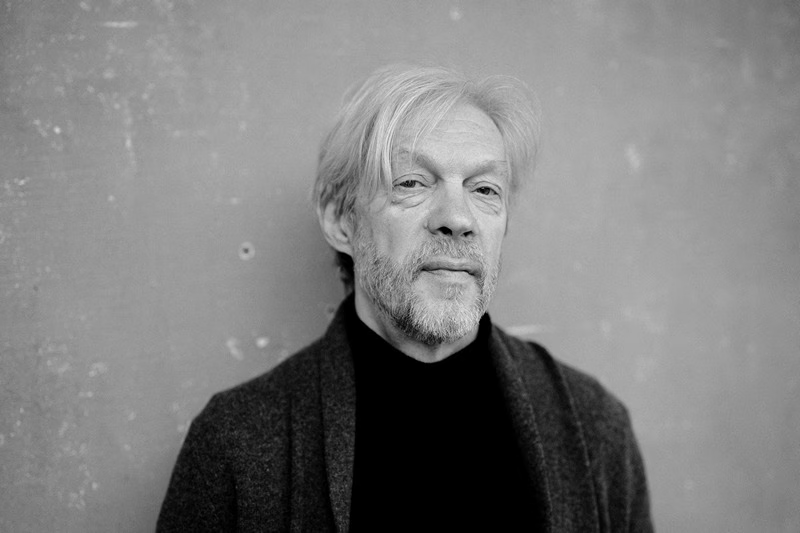

Maksim Zhbankou. Photo: from the Facebook

Which program tracks have become the most important?

There were departments for philosophy, literature, modern history and journalism. And we didn’t just voice themes — we shaped them.

No philosophical dictionary existed before we created one. There were no translations of the latest relevant literature; they emerged as a result of our work.

The field of new journalism didn’t exist before us — it took shape afterwards.

In fact, we laid the foundations for almost all of Belarusian culture’s significant projects.

So, thanks to the work of the Collegium, a whole generation was raised that soon began doing its own thing.

Exactly. This occurred in a context where the prevailing official culture had died out. We brought new words, forms, and meanings into the space where emptiness was beginning to take hold.

BelGazeta, BDG and the school: Disputes over cultural dialogue

How did you personally come to analyse the cultural field?

This happened after I started writing analytical texts. Before that, I was a music and film enthusiast. My colleagues and I organised screenings of foreign films at the Palace of Trade Unions, with support from the relevant embassies. I had to promote them in the independent press, so I started writing. First, about cinema; then, music and literature. And suddenly, I realised that significant changes were taking place and great things were happening. A fresh generation of creators had arrived, yet almost no one was saying anything meaningful about them. That was my challenge: to make the new culture visible.

Did you have any reference points, examples?

The texts of Ihar Babkou and Valiantsin Akudovich had a strong influence on me. The kind of thinking in action was beautiful and aphoristic, with a hint of rock ‘n’ roll. I realised that I would never write philosophical treatises or poetry. But I can reach some highs in analytical essays.

What was your debut?

It was an article called “The Culture of Garbage and the Garbage of Culture” for the magazine Frahmenty. I wanted to figure out why the official culture doesn’t work, and how an alternative culture could be different. Babkou translated the text into Belarusian, adding a few apt terms. That’s how my Odyssey as a cultural analyst began. For a long time, I was on my own because no other authors could fully comprehend the situation. It was the true loneliness of a samurai — a task that had to be carried out because nobody else was willing or able to do it.

Has your feeling of loneliness grown stronger since you took charge of the cultural side of things at BDG[3]?

I started my career in journalism a little earlier. At first, I worked at Belgazeta. Aliaksandr Mikhalchuk was the deputy chief editor there. We would have get-togethers with our mutual friend Andrei Fiadorchanka in the café of the famous Karavai store on Victory Square. We chatted and swapped films. One day, Mikhalchuk said, “Let’s publish your conversations about cinema on the last page of the newspaper!” That’s how Andrei and I began working on controversial film-related dialogues. It was beautiful and inspiring. We started to be recognised on the streets.

Maksim Zhbankou. Photo: from the Facebook

But you left the newspaper.

That’s right. Fiadorchanka got married and left the country, and I had a disagreement with editor Vysotski. That’s how I found myself with BDG. Legendary editor Piotr Martsau gave me complete freedom. His trust was absolute and inspiring. I began to develop the culture section in my own way. I recruited Budkin, Strelnikau and Sviardlou. Viktar Pazniakou covered music. Daria Sitnikava and Tatsiana Chudak reviewed books. Our team was powerful and outstanding.

What did you ultimately achieve? What are you proud of?

In fact, we were creating an entirely new type of cultural project. We tried to level up the cultural theme and develop a new style at new speeds. It was creative, controversial and explosive — and it’s still a pleasure to look back on.

What exactly did you write about? What fascinated you, and what caused a wry smile? What were the colours of that time?

Would you like some generalisations? Readily! Here are a few points. Firstly, the situation was absolutely unpredictable. Secondly, there was a world of possibilities open to you. Thirdly, there was the complex interplay of various cultural trends.

One thing was clear: we were gradually distancing ourselves from the Empire and creating our own unique world. You may recall the metaphor from Kusturica’s Underground: the characters drink, dance and sing without noticing that the land beneath their feet has already broken off and is floating downstream. That’s how Belarusian culture worked. We lived life and had dreams. We were busy with our little projects, unaware that they all together constituted an attempt to break free from Moscow-centric dependence.

This farewell to the Empire was both vividly emotional and disturbing. Because, alongside our project Dream Belarus, there were projects run by the authorities, by Moscow, and by the European bureaucracy. Therefore, alongside the bliss, a new sense of insecurity emerged. An unpredictable multi-vector approach emerged in place of the Soviet firmness. A conceptual culture war. At the same time, attempts were being made to create a new aesthetic, a new worldview and a new form of cultural diplomacy. And all this without a central control centre!

Personalities and events that shaped the era

Can you name the people and works that came to symbolise that era?

Valiantsin Akudovich is, without question, the Godfather of Belarusian intellectualism. In a normal country, monuments would be erected in his lifetime for books such as I Don’t Exist and The Code of Absence. And how could we forget The Kingdom of Belarus: Interpretation of the Ru(I)ns/Runes and Adam Klakotski and His Shadows by Ihar Babkou? Andrei Khadanovich’s debut books are an explosion of audacious emotions and verbal buffoonery.

In the realm of cinema, Occupation: Mysteries by Andrei Kudzinenka is an epochal departure from the banal Partisanfilm[4] model.

Maksim Zhbankou. Photo: from the Facebook

In the world of music, it’s the rough sincerity of Belarusian rock: Lavon Volsky, Mikhal Anempadystau, and the whole Narodny Albom team.

At the same time, though, an astonishing number of things were done imperfectly. We were all amateurs, and nobody taught us what it meant to be Belarusian. We created new Belarusianness ourselves. Although the error rate was very high, it was precisely this chaos that prompted a further search for solutions and led to miracles.

As Valiantsin Akudovich aptly remarked, perhaps the most significant event in the country’s history is the emergence of a people like us. A community of independent thinkers and cultural activists. Creators of new maps of the world and designers of the drafts of existence.

EHU: The experience of freedom and authoritarianism

You describe your time at the European Humanities University as one of the key episodes of your life. What happened there?

Conceptually, the EHU aligned with the Belarusian Collegium’s vision of non-governmental European higher education. Strategically, however, it remained under the influence of authoritarian models — Soviet in form and kolkhoz[5]-like in essence. The Vilnius-based EHU has positioned itself as either a Belarusian university in exile or a Lithuanian private institution. This duality also shaped my attitude. On the one hand, there were excellent students and complete freedom in the classroom. On the other hand, there was the strange and often hostile attitude of the inertial administration.

Honest activist teachers like Volha Shparaha and Andrei Laurukhin constantly faced these barriers, as did I. In 2014, the democratically elected EHU Senate, of which we were members, attempted to safeguard academic freedoms and employees’ rights. Consequently, the administration simply dismissed it and got rid of the inconvenient intellectuals. Instead of showing solidarity, the elite faculty chose to remain loyal to the leadership. In miniature, it was the same scheme that Aliaksandr Lukashenka had carried out across the country in 2020. That’s why I have mixed feelings about EHU. The students have great professional potential, but the institution is rife with typical Belarusian hypocrisy.

Maksim Zhbankou. Photo: from the Facebook

What did you gain from your close encounter with young people? What are your impressions?

I have always worked with young people, and I found that EHU students were not fundamentally different from those at Collegium. One could see how their personal freedom was developing. Institutions don’t grant freedom — it can only be claimed. And they claimed it. These young people possess incredible inner beauty, energy and original thinking. Many have experienced political resistance, which is probably also the result of our educational work.

But teaching is always unpredictable. You give it your all, and the results only come back twenty years later. Still, it’s worth it. We, creative minorities, are raising the next generation of creative minorities. There is no other way.

Belarus as an unfinished project

You have said on more than one occasion that Belarus requires thought and completion. Why? Should we blame an exceptionally famous character, who is the only one who “read Bykau’s poems”[6]?

Although it’s easy to blame one person for everything, it won’t be true. Leaders act only within the limits society permits.

Belarus is incomplete because the sources of development have been blocked. In the early 1990s, the country had the opportunity to become a fully fledged European nation. However, with the consolidation of the authoritarian regime, all options have now been shut down.

The independent media has been wiped out.

The education system remains Soviet, producing generations who have no experience of intellectual freedom.

An independent business has been clamped down on.

The multiparty system has become a mere signboard for an unchanging power structure.

The regime focuses on building loyalty schemes rather than creative search mechanisms.

There are no resources available for dealing with conflict, discussion or ambiguity.

As a result, Belarus has been in standby mode for a long time, waiting for the next signal and unable to create them independently.

This indicates that the project has not been completed.

Maksim Zhbankou. Photo: from the Facebook

You say that Belarus is a nation with untapped potential. What do you mean by this?

As Mikhal Anempadystau used to say, it is “an uncertain state, an incomplete system”. Exiled, undereducated intellectuals. Smart people who have no real leverage. However, it may be for the best that they don’t have it, since it’s not clear what they would have messed up. In general, however, the outcome is the same: cultural life is weak, thinking is fragile, and management is immature. Zero prospects, stationary jumping.

Two temporal layers: 1996 and 2018

At best, we are living in 2018; at worst, we are back in 1996.

Can you make out what lies beyond these boundary signs?

2018 marks the moment just before the disaster. It was a relatively comfortable era for the creative class, with small businesses, educational projects, low-cost airlines, civic activism, literary awards, fancy coffee shops and embroidered-shirt patriotism flourishing. The authorities gave a signal: stay out of politics, and you’ll be left alone. This is how the cultural minority lived until the pivotal year 2020.

The period from 1996 to 1998 saw the rise of visionary projects and the romantic revival of national design. That was precisely the “Independent Dream Republic”. A self-sufficient thought process. These were areas of shared hallucination and visions of the impossible. Akudovich, Mikhail Bayaryn, Uladzimir Matskevich and Todar Kashkurevich all worked on their ideas without waiting for them to be realised in society.

Akudovich was absolutely correct in his essay “Without us”: the country lives outside our plans, while we live outside its reality. This situation has persisted today. Our texts are like singing through a window — will they hear us? But we can’t but not sing. We can’t live without these songs!

This suspension, floating in space without knowing where you are going, how can you live with that? Is there a way forward?

You have to learn to embrace your own discomfort. To like uncertainty and ambiguity. They help us see reality as it is and become more resilient. Not everything we plan comes true. Reality always corrects our dreams and translates desire into possibility.

Intellectual work is an endless journey, the bliss of Sisyphus. You won’t be able to stop at some point. It’s a job forever. Such is fate. We must think, feel uncomfortable and be controversial. This creates the potential for movement.

Perhaps the crux of the matter is that our generation lost its sense of purpose after 1996? We’ve been pushing a rock for thirty years, yet nothing has changed.

Once again, I see the urge to reduce everything to a political joke. But it’s not that simple. Harmony is not guaranteed, even if we wait long enough for the first person to change. No. An all-encompassing festival of new wars will take place, involving the redistribution of property, struggles for power, seizures of financial sources, cultural disputes, the unpredictable torrent of mud and debris, and the explosion of the unpredictable. Forecasts are lying. All projects are a lie.

Therefore, the value of intellectual work lies not in the results, but in the ability to generate inconvenience, controversy and novelty. This is what Uladzimir Matskevich does, for instance. I often find myself in disagreement with him, but I am grateful to him for having the courage to speak his mind. After all, this provides a reason to think.

Maksim Zhbankou. Photo: from the Facebook

So, the important thing is to keep going and push the stone further?

That’s right. This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try. Thanks to our efforts, we have managed to preserve our status as an intellectual minority and a role model for a new generation. There is also a private thrill in it: it’s beautiful to be uncomfortable, essential to be wrong and exciting to be controversial.

We’ve been living with this palette of possibilities since the nineties. We still can afford to think and to be significant. It is natural to have doubts about our appression. After all, the value lies in becoming the foundation. And if there is a foundation, anything can grow.

Belarus, transit, dance in the void

In your outstanding vocabulary, there are many nouns and verbs with the prefix “under”: underthought, underdone, and so on. But perhaps this is a Belarusian peculiarity? Maybe we can turn what is undergiven into our own aesthetic.

I’ll refer to a song from Narodny Albom again: “I’m on the edge, I’m walking on a blade…”. This is the Belarusian transitivity. We are a nation living at road forks and crossroads, surrounded by controversial influences and external trends, cultural syntheses. And this is a strong position.

We shouldn’t build an isolated fortress. On the contrary, we need to be more open, embrace influences and develop a patchwork identity. Like Americans, they draw their strength from a combination of resources and influences that enhance rather than destroy their essence. The prospect of an open, disputing and controversial community in Belarus is also a possibility. That’s why I say that the diaspora is not a sign of a loss, but an expansion.

Emigration may be traumatic, yet it also provides an opportunity for a new beginning.

We are back to the situation of the early nineties: dancing into the void and flying without a parachute, but with room to manoeuvre. It’s dangerous and wonderful at the same time.

The project “Voice of the Freedom Generation” is co-financed by the Polish Cooperation for Development Program of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland. The publication reflects exclusively the author’s views and cannot be equated with the official position of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland.

[1] Ihnat Kancheuski (pen name: Ihnat Abdziralovich) was a Belarusian poet, philosopher and publicist who is regarded as a leading thinker within the Belarusian independence movement of the early 20th century.

[2] The Belarusian Collegium is an educational and cultural project founded in 1997 in Minsk by Belarusian non-governmental organisations and private individuals. Its aim was to create a space for intellectual inquiry, critical thinking, and the development of new directions in the humanities and social thought. Until 2015, it operated through three departments — philosophy/literature, modern history, and journalism/media studies (later joined by European studies). Since 2019, the project has taken on an international dimension.

[3] Belorusskaya Delovaya Gazeta — a Belarusian socio-political newspaper founded in 1992. Since 2006 exists in online form.

[4] An informal nickname for Belarusfilm, the main film studio of Belarus, known for producing numerous World War II films that portray Soviet soldiers as heroic and morally flawless figures.

[5] Collective farm in Soviet Union that was supposed to be voluntary in nature but forcefully removed land and cattle from peasants who were then supposed to work at kolkhoz to receive pay in kind — typically grain, produce, or other goods rather than money.

[6] A reference to Aliaksandr Lukashenka, who in a 2002 talk show interview, said he “grew up on the poems of Bykau”. Vasil Bykau was a prominent Belarusian dissident and author of novels and novellas about World War II. He never wrote poems.

@bajmedia

@bajmedia